BONLAB BLOG

Thoughts

&

Scientific Fiction

Stefan Bon receives Warwick Award for Teaching Excellence (WATE)

The Warwick Awards for Teaching Excellence (WATE) are handed out annually by the University of Warwick (UK) and aim to recognise those who have made a difference to the student learning experience through their work and their teaching practice. This year there were over 400 nominations by staff and students.

After an extraordinary academic year (2020-2021), WATE will be celebrating stories of ’everyday excellence’ in challenging times. Award winners are recognised for their exceptional commitment, impact and innovation to higher eduction by supporting students and colleagues, planting the seeds for future approaches to teaching and learning as we emerge from the global COVID pandemic.

One of the recipients this year of an individual Warwick Award for Teaching Excellence (WATE) is prof. dr. ir. Stefan Bon, a chemical engineer with expertise in polymer and colloid science, who works in the Department of Chemistry within the Faculty of Science, Engineering, and Medicine.

Prof. Bon is passionate about and dedicated to education, has an excellent relationship with the students, and has a track record to innovate in and to deliver great learning environments and experiences for students at Warwick. Throughout the years he has delivered original and exciting modules in polymer and colloid science, thermodynamics, kinetics, mathematics, key skills, and chemistry practical lab classes.

His creativity, drive, and passion to teach science and his engagement with the student community have led to progressive educational ideas being implemented at Warwick University, amongst which Chemistry Café, a highly successful student led social informal learning space, a concept now rolled out to multiple departments.

Prof. dr. ir. Stefan Bon says: “ This award came as a total surprise. I am absolutely delighted to have been nominated by our students and I am thrilled that the WATE committee decided to make me one of this year’s WATE recipients. I truly feel touched by this, it means a lot.

I would like to say a massive ‘thank you’ to all the students for their enthusiasm and dedication to their studies, standing up for themselves and each other, and forming together the Warwick community, especially in these unusual and difficult COVID times. I am proud of what they have achieved, especially in this academic year.

Teaching science is a key reason why I became an academic. The opportunity to mesmerise people with scientific concepts and see them use and apply these with enthusiasm to discover new science and develop innovative strategies for a more sustainable society, makes me very happy.

The combined learnings from teaching over one academic year remotely/blended, together with the STEM-grand challenge plans Warwick University has for the sciences, is a not to be missed opportunity to provide a step-change in higher education delivery.”

Prof. Bon is contributing actively to this with colleagues from across the University and is leading a task group under the Education and Students Experience Work Group, to look at new and exciting learning opportunities and curriculum design and how these can be implemented for Warwick science.

Replacing titanium dioxide as opacifier: consider a shape change

A fresh lick of paint breathes new life into a tired looking place. Ever wondered how a thin layer of paint is so effective in hiding what lies underneath from vision? Beside colour pigments, and a binder that makes it stick, paints contain microscopic particles that are great at scattering light and turning that thin layer of paint opaque. The golden standard for these opacifiers is small titanium dioxide particles, of dimensions considerably smaller than one micron. Their use is not without controversy, as they pose a significant environmental burden, with a substantial carbon footprint and a questionable impact on human health. Ideally, though, titanium dioxide should be replaced, but the list of safe, high refractive materials is very limited. Here we provide a potential solution.

A fresh lick of paint breathes new life into a tired looking place. Ever wondered how a thin layer of paint is so effective in hiding what lies underneath from vision? Beside colour pigments, and a binder that makes it stick, paints contain microscopic particles that are great at scattering light and turning that thin layer of paint opaque. The golden standard for these opacifiers are small titanium dioxide particles, of dimensions considerably smaller than one micron. Their use is not without controversy, as they are a big environmental burden, with a large carbon footprint and a questionable impact on human health. The reason why titanium dioxide particles are great at scattering light is that they have a high refractive index compared to the other paint ingredients, so when distributed throughout the dried paint film their hiding power of the underlying surface is fantastic. When no coloured pigments are used, the coated surface appears then whiter than white.

Ideally though, titanium dioxide should be replaced, but the list of safe high refractive materials is very limited. This makes you wonder if there is another handle, beside refractive index? Can we design efficient scattering enhancers from materials of lower refractive index?. Inspiration came from the white Cyphochilus beetle, native to southeast Asia. The scales of the beetle are not made of high refractive index materials, but they thank their white appearance to an intricate anisotropic porous microstructure, resembling the bare branches of a dense bush.

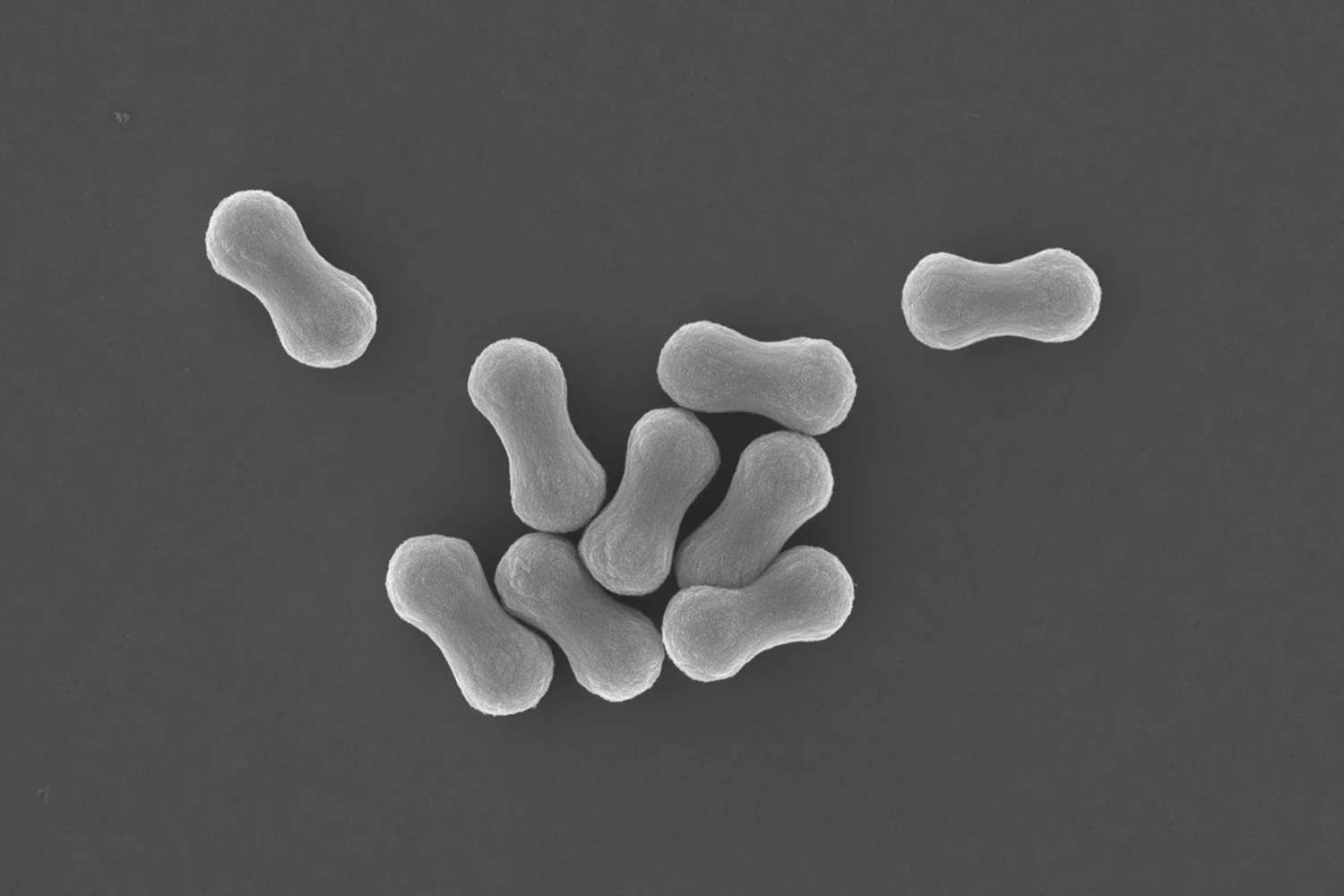

We at BonLab formed a team where researchers dr. Brooke Longbottom and dr. Chris Parkins together with dr. Gianni Jacucci and prof. Silvia Vignolini at the University of Cambridge (UK) designed a simplified mimic in the form of tiny rodlike silica particles and compared their scattering performance with spherical silica particles.

Our work published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry C from the Royal Society of Chemistry is part of their HOT paper collection and shows that the anisotropic silica particle outperform their spherical counterparts, and show excellent scattering performances across the visible electromagnetic spectrum when casted as a film.

SEM images and optical characterization of white silica supraparticles. a) low magnification SEM image of supracolloidal balls, b) higher magnification image of single supracolloidal balls, c) supracolloidal ball assembled in the presence of 0.01 M calcium chloride. Scale bars: a) = 15μm b&c) = 10μm. d) Reflectance spectra comparing the scattering properties of supraparticles with films of silica rod particles of similar size (thickness of 25μm). Supraparticles show performance comparable to the corresponding films. Increasing the disorder reduces the scattering efficiency. The reflectance spectra for the supraparticles were measured using a microscope, while for the film they were retrieved from the total transmission data.

We did not stop there, and went a step further to develop a prototype of a new class of micron-sized hiding pigment. We took these rodlike silica particles and assembled and sintered them into stable porous supracolloidal microspheres, as can be seen in the image above.

Prof. dr. ir. Stefan Bon says: “This work has been a number of years in the making. It was an absolute pleasure to work with prof. Silvia Vignolini and her team. We are very happy with the end result. We hope that this new type of hiding pigment provides inspiration to those who wish to replace titanium dioxide. After all, there is more to opacifiers than refractive index.”

The paper can be accessed from here:

https://doi.org/10.1039/D1TC00072A

BonLab fabricates textured microcapsules through crystallization

Watch the Talk by clicking here.

Microcapsules can be found in a range of commercial applications, including cosmetics, healthcare, agriculture, and food. The capsules serve as a storage vessel for an active ingredient, for example a nutrient or fragrance. They can have a variety of designs, the simplest form being a single internal liquid-based core surrounded by a solid shell. The chemical and physical characteristics of this shell influence the colloidal stability of capsules in formulations, dictate the permeability and mechanical robustness of the capsules, and can potentially regulate substrate adhesion. Beside storage, these features of the microcapsules are there to regulate and control release and delivery of the active compound.

A considerable part of the technologies used to produce microcapsule relies on the use of synthetic polymers that do not break down, with terrible consequences for environmental build up. One way is to make use of biocompatible and degradable plastics.

We provide an alternative solution, in that we fabricate the capsule from small molecular compounds, instead of polymers, that can crystallize.

Microcapsules can be found in a range of commercial applications, including cosmetics, healthcare, agriculture, and food. The capsules serve as a storage vessel for an active ingredient, for example a nutrient or fragrance. They can have a variety of designs, the simplest form being a single internal liquid-based core surrounded by a solid shell. The chemical and physical characteristics of this shell influence the colloidal stability of capsules in formulations, dictate the permeability and mechanical robustness of the capsules, and can potentially regulate substrate adhesion. Beside storage, these features of the microcapsules are there to regulate and control release and delivery of the active compound.

A considerable part of the technologies used to produce microcapsule relies on the use of synthetic polymers that do not break down, with terrible consequences for environmental build up. One way is to make use of biocompatible and degradable plastics.

We provide an alternative solution, in that we fabricate the capsule from small molecular compounds, instead of polymers, that can crystallize.

Artist impression of textured microcapsules made through crystallization.

In our work, published in the scientific journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces we focus on the fabrication of microcapsules of which the capsule wall is composed of an inter-locked mesh of needle-like crystals, which besides capsule rigidity and semi-permeability, provides a roughened surface texture.

In this proof-of-concept study crystals of the small organic compound decane-1,10-bis(cyclohexyl carbamate) are formed within the geometric confinement of emulsion droplets, through precipitation from a binary-solvent dispersed phase. This binary mixture consists of a volatile solvent and non-volatile carrier oil. Crystallization is facilitated upon supersaturation due to evaporation of the volatile solvent. We show that the microcapsule diameter can be easily tuned using microfluidics.

The technology is shown to be scalable using conventional mixers, yielding spikey microcapsules with diameters in the range of 10-50 μm. We highlight that the capsule shape can be molded and arrested by jamming using recrystallization in geometric confinement.

With an eye on commercial applications we show that these textured microcapsules show enhanced deposition onto a range of fabric fibers. They outperform their traditional polymeric analogues by sticking better on fibrous substrates.

Prof. dr. ir. Stefan Bon says: “I am delighted with this work, a coordinated effort which was led by first author dr. Sam Wilson-Whitford. A while back we decided in BonLab that our science needed to be greener, and more sustainable. We think our way of making textured microcapsules meets these criteria. We hope that it inspires industry, and that the concept will prove to be useful across a variety of application areas.”

The paper can be accessed here:

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsami.0c22378

A talk on the topic can be accessed here:

https://www.formulation.org.uk/pc20programme/250-past/2021/pc20/860-pc20-bon.html